Time was when Black singers were not welcome on U.S. opera stages, or black audiences in many classical-music venues. The story of Marian Anderson’s historic concert at the Lincoln Memorial when the Daughters of the American Revolution denied her the use of their Constitution Hall says as much about Black resilience as it does about White resistance, but even after that historic event, it took far too long for inclusive practices to take hold. When Black talents too brilliant to be ignored blazed new trails, they were often cast in exotic roles or expected to hide their Black-ness behind layers of white pancake. Mercifully, those bad old days are largely behind us.

Today’s opera pantheon is filled with undisguised Black faces, and impresarios and industry leaders are now racking their brains to bring in the very audiences their predecessors worked to keep out. The classical-vocal landscape is infinitely enriched by the talents of artists ranging from Angel Blue to Pretty Yende (I’m sure there’s a Z-name out there, but I can’t come up with it off the top of my head), and audiences of color can now regularly (though still not regularly enough) expect to see people who look like them onstage.

For Black History month, I thought I’d share a random selection (very random) of Black artists of the past. (For singers of today, I leave it to you to check them out in a live performance — or, if the nearest opera house is too far away, you can always catch a Met radio broadcasts or Met Live in HD transmission at your local movie theater. Soloman Howard doubles as the Marquis and the Padre Guardiano in the radio broadcast and HD transmission of La Forza del Destino on March 9; March 23 brings Roméo et Juliette with Will Liverman as Mercutio, Alfred Walker as Frère Laurent and Frederick Ballantine as Tybalt; and Angel Blue stars in La Rondine on April 20. Details at: https://www.metopera.org/season/in-cinemas/.)

I’ll confine myself to three selections per voice category. Please don’t be offended if I’ve left out your favorite singer of color. We’ll start at the top, with the sopranos.

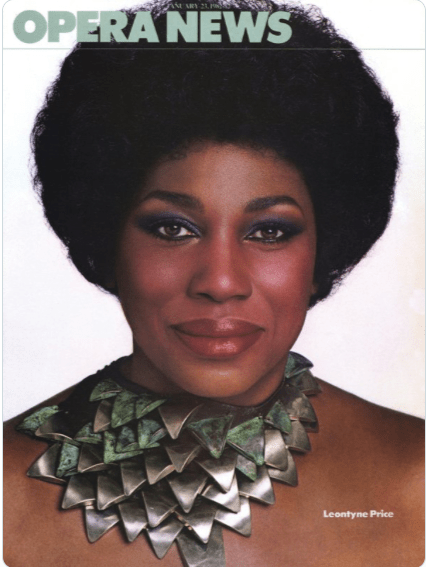

Comparisons, as Shakespeare’s Dogberry observed, are odorous, but I doubt I’d get too much argument if I said LEONTYNE PRICE was the best of the best. All the most appealing adjectives in the lexicon of the opera critic — creamy, velvet, radiant, plummy — pile themselves up on one’s tongue in the attempt to describe her timbre. Her breath control was astounding, her legato utterly seamless, her portamento mesmerizing, her musical instincts unerring. She projected a sense of unshakeable integrity and self-possession, a sort of personal grandeur that ideally suited many of the classic diva roles.

I was in the same room with Price only once, when she arrived at the Pierre Hotel to receive her Opera News Award. As she entered the hall, we were all surprised by how small she was—she had always seemed a towering figure on the stage — but when she opened her mouth to sing a few phrases during her acceptance speech (at the age of eighty-one!), she was ten feet tall. In a Met career that spanned three decades, Price sang everything from Mozart to Puccini to Tchaikovsky’s Tatiana to the world premiere of Samuel Barber’s Antony and Cleopatra. But it was in the music of Verdi that she shone with the most intense luster. By my count, she sang a half-dozen of his works at the New York house, and nobody ever sang them better. Here she is as Leonora in La Forza del Destino. The character’s fraught history makes this plea for peace all the more heartrending in the context of a complete performance, but even excerpted in concert, Price’s rendition is so resonant with spiritual intensity that one can only respond with a fervent “Amen!”

RERI GRIST, a native New Yorker and graduate of the High School of Music and Art and Queens College, started out on Broadway as a child performer, appeared in Carmen Jones, and was the first Consuela in West Side Story. Leonard Bernstein chose her as soloist for his recording of Mahler’s Fourth Symphony, and she sang it again on his Young People’s Concerts series. The rest is history. Her sparkling soprano and engaging stage persona took her to most of the great theaters of Europe, and to the Met, where she bowed as Rossini’s Rosina in 1966.

Heard here in Zerbinetta’s mind-bogglingly challenging aria from Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos, Grist is the epitome of grace and poise. She makes Strauss’s wild flights of coloratura sound like a walk in the park, while also managing to capture a charmingly innocent sense of freedom and frankness, eschewing the vampishness that sometimes flattens this rich character into a caricature. The touch of acidity in Grist’s otherwise sweet, bell-like tone, along with the restraint of her stage presence, tells us that this Zerbinetta is no ditsy flirt playing devil’s advocate but a woman of substance expressing her well-considered philosophy.

MARTINA ARROYO, a Harlem native of Puerto Rican descent, won the Metropolitan Opera Auditions in 1958 and was a mainstay of the company for decades. Known for the enveloping warmth of her voice and personality, she was as comfortable cracking jokes on Johnny Carson as she was knocking out the blockbuster roles of Verdi and Puccini. (When singing Cio-Cio-San, she once referred to herself as “Madame Butterball.”) A Washington Post profile by Anne Midgette called her “down-to-earth, riotously funny, and not at all diva-esque,” a description that was certainly borne out by all her interactions with Opera News during my time with the magazine. Arroyo’s contributions to the opera world go far beyond her onstage exploits: for decades, her eponymous foundation has provided emerging artists with the tools they need to develop complete opera roles and navigate an opera career.

In Donna Anna’s daunting “Non mi dir,” from Don Giovanni, such is the completeness of Arroyo’s technique that a listener may not even notice the vocal hurdles as Arroyo sails through them. In a piece that often comes across as a lengthy and sour-pussed brush-off, Arroyo reveals it as what it is—a lover’s gentle plea for understanding and forbearance. Her pearly tones never turn harsh or strident; her big voice stays ideally flexible and responsive under pressure, and her mastery of the musical challenges leaves her free to focus on expressing the character’s vulnerability, grief and tenderness, resulting in that rarest of phenomena—a likable Donna Anna.

If you loved listening to these great ladies, rush to your nearest streaming app and look up Roberta Alexander, Kathleen Battle, Harolyn Blackwell, Dorothy Maynor, Jessye Norman and the countless other brilliant Black sopranos of the past who paved the way for today’s stars. You will need a lot more than a month to catch up on the glorious history of Black performers on the opera stage.

Next up on the blog: a handful of my favorite black mezzos and contraltos.

Leave a comment