My sister and I grew up in East Hampton — sort of. We were five when we took our first family vacation there, and we felt at home from the moment we arrived. At the time, it was just a sleepy little bayman’s town, where the features for visitors were pristine beaches (nearly deserted even in the high season), roadside farm stands (corn a dollar a dozen!), and a few restaurants on the waterfront, all family-run, where you could get a good seafood dinner for about 1/2 the price of what it would have cost in the big city. The shops on Main Street were quirky little establishments selling things like handmade children’s clothing and big squares of gingerbread, or penny candy and animal puppets, or moccasins and jewelry made of wampum and scrimshaw. The bookshop and the liquor store had resident cats. Dreesen’s Market had a famous doughnut machine, which you could watch in operation through the plate-glass window, auto-flipping the little golden rings, before going inside to get your plain, powdered sugar and cinnamon doughnuts straight out of the hot fat, along with a cup of coffee and a copy of the East Hampton Star — all that was needed for a perfect morning on the beach.

There was no such thing as “The Hamptons” back then; there were Westhampton, Hampton Bays, Southhampton, Bridgehampton and East Hampton, all very distinct entities with their own idiosyncratic personalities. The reason Dan’s Papers is called by that silly plural name is that back in the day editor/publisher Dan Rattiner put out separate newspapers for the different villages — The Montauk Pioneer; The East Hampton Summer Sun…. We vacationed in East Hampton every year — a blissful two weeks at the Three Mile Harbor Inn, a small scattering of cottages just off the road, where I swear to you the first year the cabin we stayed in cost $25 a night for the four of us. It came with a parking pass for the town beaches; we had to buy our own $20 pass for the village ones. (For comparison, the town permit now costs $600 for the season; the village one is $750, or $300 just for one month.)

Our little paradise had one big room that contained a kitchenette (full-sized stove and fridge!), a double bed and two twins, plus a tiny bathroom. There were picnic tables and grills outside on the grass, so one could dine under the stars. If it rained, we went to Ma Bergman’s, where the front porch was open but covered, the atmosphere was family-friendly but elegant, and the thin-crust pizza (unheard of elsewhere at the time) was sensational.

The cabins had a special feature: a few steps down the little side road was the beginning of Three Mile Harbor, a marsh-edged body of water that offered the best sunset views ever. (At the crack of dawn, it also offered wildlife galore — herons, swans, bunnies, egrets, the works — but only my father ever took advantage of it; the rest of us slept in.) Every evening, Dad would light the grill, and we would all take our cocktails (martinis for the parents, grape soda from the IGA for us kids) down to the end of the road and marvel at the glorious sky until the fire was ready for cooking.

It was a wonderfully simple life. Days were spent at the beach (we liked to hit the ocean in the morning and the bay after lunch); evenings we either barbecued for ourselves or enjoyed fine dining with spectacular views at the Silver Seahorse or Georgette’s or, a little farther afield in Montauk, Gosman’s Dock. The views were stunning, the fish was fresh, the air was salty and the prices were rock-bottom.

Though we only spent two weeks out there every year, we felt and acted like locals. Dad covered the car with bumper stickers that said “Bonac Against the World, Bub” (the townies were called “Bonackers” after Accabonac Harbor) and “I Believe Dan’s Papers.” (Dan’s colorful and whimsical publications were full of dubious stories such as a report on an annual nude women’s volleyball game whose location was top secret.) We’d been staying at the same place and going to the same restaurants for as long as we could remember. Dad followed town and village issues in the Star or by chatting with Mrs. Ambrose, who ran the inn. As the years went by, we agonized along with the locals over the gradual changes to the neighborhood; we felt the losses of our favorite businesses and the changes in the area’s character as deeply as anyone who actually owned property out there. We kept taking those family vacations long after we’d grown up, and the yen to be a real local got stronger every year.

By the time we finally got our own place (nearly a half-century after we first arrived), the picture had changed radically. The Main Street knickknack shops have been replaced by high-end citified establishments such as London Jewelers and Prada and four or five business all owned by Ralph Lauren or his relatives. Farm-stand corn (when you can find a farm stand) is now a buck-an-ear (sheer piracy!) Those bargain waterfront restaurants will now run you easily $100 a person, and the simple local seafood menus have given way to over- imaginative super-chef concoctions that would bury the delicate flavor of the fresh fish and produce if most of the menu items weren’t imported from afar. The baymen are few and far between these days, pushed out by the rich and famous who have made their playground where these honest fisherfolk used to make their living.

But if you try hard, you can still get a whiff of the Bonac life. There are a few beaches left that the “in” crowd hasn’t discovered, where the sparkling sand and glittering water outshine the brightest pop-culture star.

A few of the local churches still have quaint summer fairs on their big front lawns, as does the Ladies Village Improvement Society. Gosman’s Dock has expanded and evolved but retained its authentic fishing-village character. Bostwick’s on the Harbor still has a beach-town vibe and feels as welcoming to a family on vacation as to a Hamptons celebrity. The Springs Tavern and Grill, right around the corner from us, has gone through many transformations since its original iteration as the Jungle Inn, storied hangout of local artists including Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, but it still feels like a hometown watering hole, where everyone knows everyone else, and the idea of the good life doesn’t hinge on how many millions of dollars you have in the bank. The East Hampton Star, the best local newspaper I have ever encountered, is one of the most vital remnants of the real town, consistently full of timely information about local events and carefully reported articles that keep one up on the always-intriguing political scene. (The office, on Main Street, has a stained-glass ceiling!)

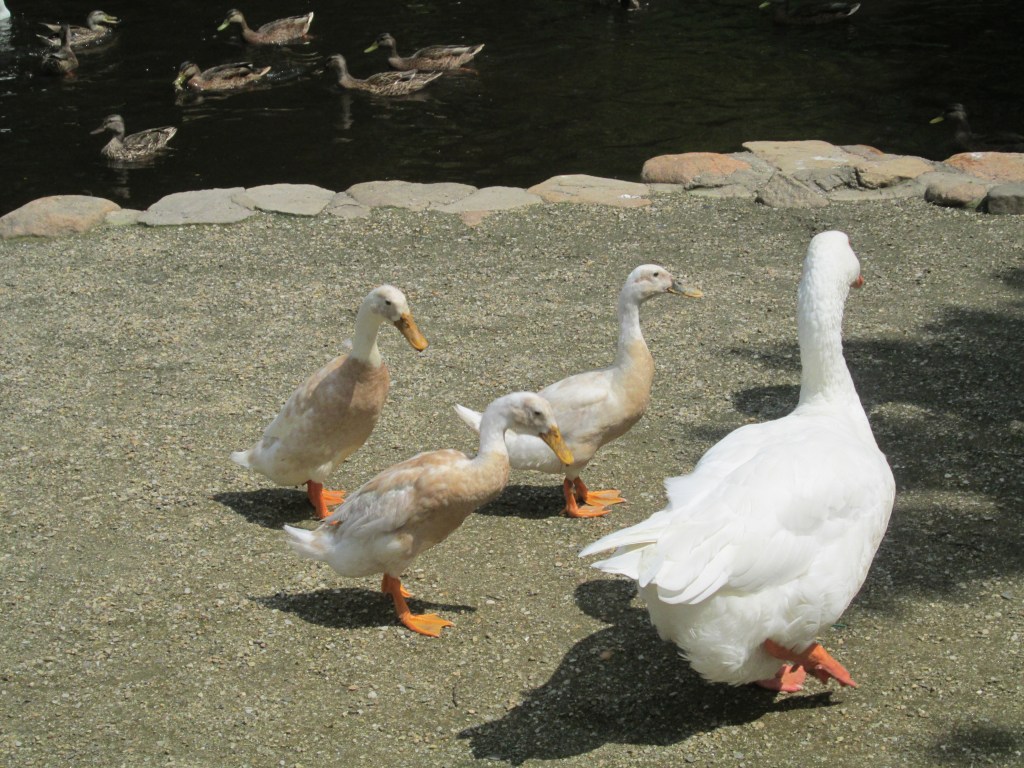

The duck pond and nature preserve remains a delightful, no-frills, wholesome and irresistible outing for kids of all ages — and it’s absolutely free!

Above all, there is still the incredible natural beauty that lured all those famous artists in the first place. A lot of the old East Hampton is gone, but the way the light hits the harbor hasn’t changed, and it still thrills my bonac heart every time I look at it. They can’t take that away from me.

Leave a comment