I was heartbroken to learn of the death last week of Sir Donald McIntyre, one of my operatic idols. It may seem odd to be in deep mourning for a man I met only twice, but McIntyre’s performances were so three-dimensional, so fully human, so richly detailed that after watching him onstage, one felt one knew him to his core. And after an hours-long one-on-one interview and an extended post-performance chat in his dressing room, that impression — of a man of towering presence, immense humanity, deep humility and unfailing gemütlichkeit — was even more distinctly etched.

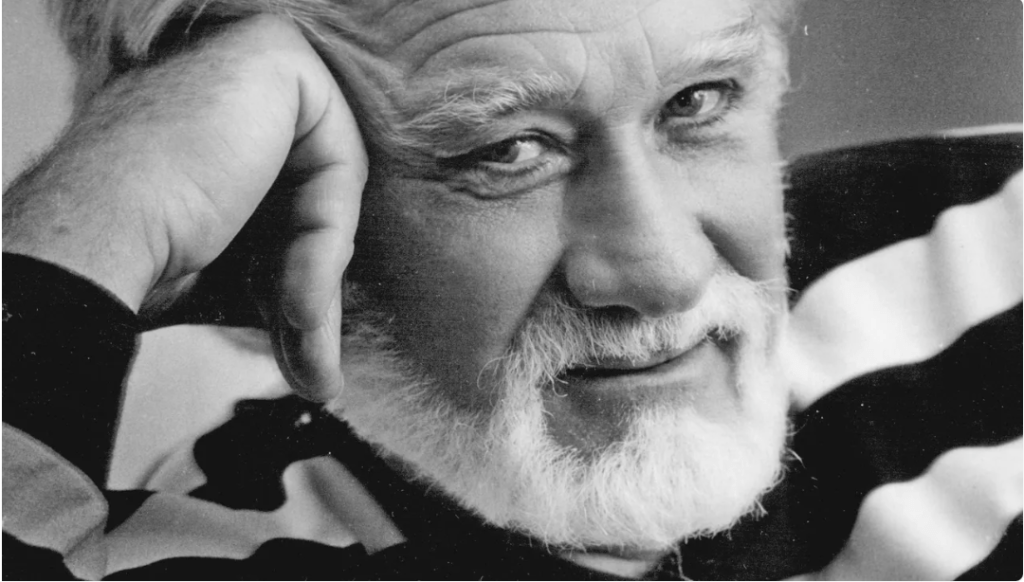

With his trademark mane and beard, McIntyre looked like a cross between Moses and Santa Claus, and his dramatic range was equally diverse. He had all the gravity and willfulness of the Norse Gods, all the generous nobility of heart of King Marke and gemütlichkeit to spare of the likes of Hans Sachs and Figaro.

When I interviewed Sir Donald thirty years ago, he told me singing in his native tongue, as he did during his formative years at Sadler’s Wells, had helped him develop his acting chops. “I think most of the difficulties of young singers being dull or colorless spring from the fact that you’ve got so much to cope with when you’re learning everything at once — trying to develop your voice and your acting and get the pronunciation right,” he said. “In your own language, the expressive side comes so much more naturally.” He proves his point here, as an English-language Figaro lamenting the supposed betrayal of his bride-to-be, his amazingly sharp diction making every word and emotion crystal-clear.

McIntyre’s best-known assumption was Wotan in the Ring cycle, which he sang around the world, including in the first-ever telecast of Wagner’s epic, live from Bayreuth. In the final scene from Die Walküre, McIntyre tempers the hotheaded willfulnesss of the youthful Rheingold protagonist with the devastating angst of a leader whose own laws oblige him to make agonizing compromises and the ineffable tenderness of a father whose discipline inflicts more pain on himself than on his child. In the once-controversial, now iconic Patrice Chéreau production, McIntyre’s voice rings with a touching combination of regret and paternal pride, and his body language, exquisitely attuned to Wagner’s grand-scale timing, expresses the emotional inflections in the music as symbiotically as a dancer in a ballet, wringing every micro-ounce of catharsis from the drama.

When McIntyre was onstage, the audience hardly dared breathe, lest they miss some subtle touch in his performance. His riveting gift for storytelling is on vivid display in this excerpt from Parsifal. The old knight Gurnemanz’s description of Klingsor’s descent into evil — from sinful desire, through misguided atonement by self-mutilation, to the mastery of black magic for his evil ends — exudes horror at the villain’s deeds, fascination with the story and pity for the sinner.

McIntyre gave even the worst of the baddies relatable inner lives. Opera News Senior Editor John W. Freeman described his Klingsor as “more fallen angel than driven fiend.” His Méphistophélès in Berlioz’s Damnation de Faust has a scorching sense of humor. And when McIntyre sang conflicted characters agonizing over their bad choices, he was downright heartbreaking. Golaud, in Debussy’s deliberately obscure Pelléas et Mélisande, is a case in point. Golaud’s jealous spying and vengeful fratricide are rendered almost understandable in McIntyre’s performance, which lays bare the hidden places of his soul and elicits instinctive sympathy, while the title characters remain elusive, wrapped in Debussy’s vague and fragrant ambiguity. In this opening passage, Golaud, lost in the forest, encounters the weeping and mysterious Mélisande and is drawn to her. Golaud’s courage, tenderness, compassion and human kindness are rendered so indelibly in McIntyre’s psychologically pitch- perfect performance that his violent throes of jealousy at the end are more to be pitied that censored.

McIntyre was one of those artists whose characterizations were so right that one never wanted to watch anyone else in one of his roles. Once seen, he couldn’t be replaced. He was a terrifyingly unhinged Cardillac, a blackly brooding Klingsor, a gleefully malicious Nick Shadow and a towering, doom-wracked Dutchman in Václav Kašlík’s wonderfully wacky film version, in which he played the opening scene hip-deep in water..

In Arabella at the Met, as the heroine’s inveterate-gambler father, whose sincere hopes for his daughter’s happiness are continuously sabotaged by his addiction, he stole the show so entirely from Kiri Te Kanawa’s lovely title character that the opera could have been rechristened “Count Waldner.” The whole delightful performance is available on demand on the Met’s website: https://ondemand.metopera.org/performance/detail/51916e08-5cfa-50f7-a7fc-c177e48b6d84

But the role that best represented every facet of McIntyre’s radiant soul was Hans Sachs, a portrayal that achieved a pitch-perfect blend of warm-blooded realism and fairy tale fantasy. McIntyre made Sachs precisely the kindly, generous, wise and balanced father-figure one always wanted to believe in without stinting the agony of the character’s own very human desires and sacrifices. The irresistible twinkle in his eye was offset by the occasional glint of anger and moreso by the immense sympathy with which he viewed all his fellow beings in their folly. The moment of impetuous fury in which Sachs rails against the madness of the world before giving up his own romantic dream was surprisingly intense but emerged as his way of clearing a path in his soul to give up Eva without regret or acrimony. In the excerpt below, Eva (Karita Mattila), whose father has given her as the prize in the Mastersingers’ song contest, comes to the cobbler Sachs’s workshop under the pretext of a pinching shoe. She is angry that he has apparently declined to help her innamorata win her — or at least to vie for her himself. Sachs, of course, has already arranged for her perfect happiness at the expense of his own dreams by not only stepping aside but teaching his hotheaded young rival how to write the winning song. The pirated live-performance clip is woefully out of focus, but it’s the only video I can find of what was possibly the greatest characterization I ever saw.

Leave a comment